How to Start a Clothing Line: Secrets from a Project Runway Designer

When Sarah Donofrio collected her degree in fashion design, she stepped into the real world with the same question that has troubled creatives of all ilks: what now?

Fashion school taught Sarah about pattern grading, sewing, drawing, and draping. She could drop a mean French seam. She could tell you everything about fit. Her education, however, didn’t prepare her to actually start a successful clothing line. These are skills she’s learned over the past 15 years while she working for other clothing brands and through launching her own business.

How do you follow Sarah’s path and start your own clothing line? To take your dream from a business idea to launch and make it in the frenzied world of fashion takes a specific set of skills, a generous dose of creativity, and a pinch of business savvy. And did we mention passion and drive?

Sarah is the perfect case study for this guide to starting your own fashion business: she has lived and worked in two countries, and her experience spans design, production, education, ecommerce, wholesale, consignment, and physical retail. She has struggled and thrived, sometimes simultaneously, over her many years in the industry. In 2016, Sarah was a contender on Project Runway’s 15th season. She has since re-branded her clothing business, launched One Imaginary Girl as an online store on Shopify, and opened a retail location in Portland, Oregon.

In this post, we’ll explore the ins and outs of starting a clothing line from scratch—everything from education and design to manufacturing and marketing—using Sarah’s inspiring story as the running thread.

Shortcuts 👠

- Skills and training

- Business plans for clothing lines

- Fashion trends

- Developing a fashion brand

- Inspiration

- Fashion design and development

- Clothing production and manufacturing

- Fabric sourcing and textile design

- Seasons and collections

- Wholesale and consignment

- How to start a clothing line online

- Fashion retail

- Tips from Project Runway

Skills and training for starting a clothing line

Designers like Vivienne Westwood and Dapper Dan found massive success in the fashion world, even though they were self-taught. And they started their careers pre-internet. We live in a time of access, where rebuilding an engine or tailoring a t-shirt can be learned simply by watching a YouTube video.

It’s possible to skip school and still make it in the fashion industry, but formal education, whether in a classroom or online, has its merits:learn the latest industry standards, get access to resources and equipment, make contacts, and get feedback.

While Sarah owes a great deal of her success to learning professional skills in a classroom, much of her education was gained in the real world. She left school and worked in the corporate sector, holding retail buying and product development roles for large companies like Walmart and Jean Machine. “Working in corporate, I knew I was hitting a wall,” Sarah says. “I wanted to work for myself. But I felt that it was important to get that corporate experience.”

It took me a long time to be confident enough that I could fill a store with my clothing.

School offered the technical know-how, and Sarah is an advocate for spending a few years learning the ropes from other brands and designers. “It took me a long time to be confident enough that I could fill a store with my clothing,” she says. “I think that I needed the time to grow and to get advice and experience.”

Sarah completed her education with a three-year college diploma. Many institutions offer fashion design and small business programs in varying formats. Schools like Parsons in New York and Central Saint Martins in the UK are world renowned for their fashion programs.

Shopify Compass Course: Sell Your Homemade Goods Online

Have a product you’re ready to sell? The Kular family shares their experience building a business around mom’s recipe book. From selling one-on-one to reaching the aisles of Whole Foods.

Enroll for freeIf you have more drive than funds or time, there are a growing number of fast-track and online courses for fashion industry hopefuls. Check local community colleges for formats that accommodate your schedule and budget, or consider online learning through sites like MasterClass (there’s a fashion design course taught by Marc Jacobs himself), Maker’s Row Academy, or Udemy.

Sarah now has teaching credits under her belt and used her platform as a means to teach newbies the important business aspects of fashion. When she developed her course curriculum, she ensured it was more business focused—something she felt she missed in her own learning. “We were teaching them about retail buying, about manufacturing,” she says. “In fashion, you’re not just costing fabric and buttons and labor. You’re costing shipping, you’re costing heating and rent.”

How to start a clothing line from scratch: A step by step guide

If you've been searching for ways to launch a clothing line, in this video we’ll share a step by step guide on how to start a clothing brand from scratch.

What’s your fashion business plan?

As Sarah discovered, the world of fashion and the world of business have a lot more overlap than she expected. Starting a clothing brand requires many of the same considerations as starting any business. How much does it cost to start a clothing line? When should you pursue capital? What outside help will you need to navigate legal, financial, production, and distribution aspects of the business?

Once you have a business idea, you may be able to fund it yourself, run it on the side, and bootstrap as you go. If you plan to go all in and have some upfront costs, though, you may need to seek investors or apply for a loan. A solid business plan and well-rehearsed elevator pitch will go a long way. Anticipate the questions, Sarah advises, and make sure you know your stuff.

📚 Read more: How to Write a Business Plan for Your Clothing Line

Navigating fashion trends

After leaving the corporate world, Sarah launched her namesake collection while holding down several day (and night) jobs. She pursued her passion in between bartending, DJing, and working for an upscale bridal boutique.

Through her years of developing her brand as a side hustle, she’s learned that while watching trends is extremely important, it’s equally important to focus. Hone in on your strengths and be true to your own design sensibilities. Fashion school will teach you the basics of making everything from undergarments to evening wear. “The trick is finding what you’re good at and focusing on that,” Sarah says.

I’ve always had a really good trend intuition. But it’s all about translation.

While her line has a year-over-year consistency—design choices in her pieces that are unmistakably hers—Sarah is always watching trends. She says that the key is adapting trends to your brand, personalizing them, and making them work for your customer. “I’ve always had a really good trend intuition,” she says. “But it’s all about translation.” Sarah worked on plus-size collections during her time at Walmart and said that translating trends meant also considering the needs of the plus customer.

Though she sticks to her strengths, Sarah factors what’s happening in fashion—and in the world around her—into her development. “Take athleisure,” she says. “I don’t make tights, I don’t make sports bras, but this cool woven crop would look kind of awesome with tights, so there’s how I am maybe using the trend."

Keeping her production tight and retaining control over design, Sarah recently was quickly able to pivot in the wake of the global pandemic, adding face masks in her signature prints. She sold 1,100 masks within a two-month period, and she’s turned those sales into repeat customers.

In the noisy world of fashion, consider finding niches or filling gaps in the industry like these inspiring Shopify merchants:

- Leanne Mai-ly Hilgart launched vegan winter coat brand Vaute after finding a disappointing lack of cruelty-free options on the market

- Catalina Girald’s lingerie brand, Naja, was built on empowerment and inclusiveness

- Camille Newman threw her hat in the plus game with Pop-Up Plus

- Mel Wells launched a gender-neutral vintage-inspired swimwear line

- Taryn Rodighiero also joined the swimwear game but focused on custom suits, made to order to each customer’s exact specifications

👠 Looking to sell vintage clothing online? Read our ultimate guide to sourcing, pricing, and storing vintage apparel with tips from successful resellers.

Developing a brand for your clothing line

Remember that “brand” extends beyond your logo and the design of your collection. It encompasses your values, mission, website design, photography style, personal story, sustainability statement, and more.

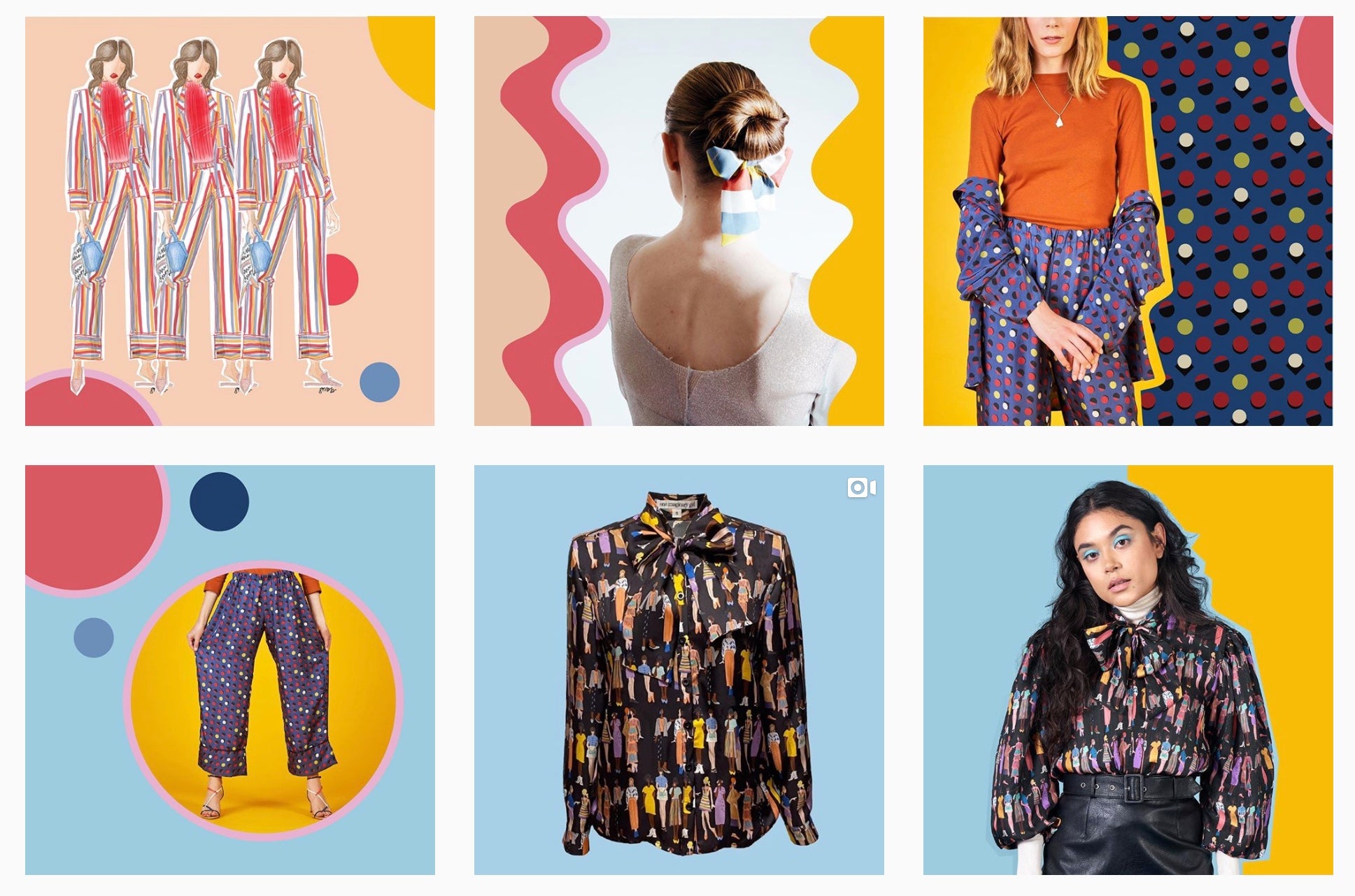

Use social media to build a lifestyle around your brand: share your inspiration and process, inject your own personality, tell your brand story, and be deliberate with every post. “The key to social media is consistency,” says Sarah. “I think you have to post every day, but it also has to be interesting.” She mixes up her content with travel, inspiration, sneak peeks at works in progress, and even some interesting stats from her Shopify dashboard.

🛠️ More resources to build a fashion brand:

- Branding Secrets from 14 Fashion Industry and Fashion Entrepreneurs

- Generate a Business Name for Your Clothing Line

- How to Design a Logo for Your Fashion Brand

Inspiration for your fashion collection

Devour fashion publications, follow style influencers, and subscribe to fashion newsletters and podcasts to stay inspired and catch trends before they emerge.

You can collect your inspiration by bookmarking, adding to Pinterest boards, or saving content you find around the web. Many creatives choose to go the tactile route with physical mood boards, bulletin boards, or sketchbook collages. Keeping your inspiration visible helps keep you motivated to pursue your dream and stay focused on the type of brand you’re trying to build.

Fashion design and development

Sarah is an advocate of the sketchbook as one of the most important tools for a designer. “I take my sketchbook everywhere with me,” she says. “As I’m sketching away, every so often I’m like, ‘Oh, this little drawing would translate really well into a repeat pattern.’” As a contender on Project Runway, she wasn’t allowed to have her sketchbook with her, due to the rules of the competition. “That really threw me off my game.”

I always use a mix of new technology and notebooks full of scribbles.

While she’s embraced technology in many ways, Sarah stresses the importance of doodling, no matter what the medium. For her, every idea starts on paper before being translated to Illustrator or another tool. “I always use a mix of new technology and notebooks full of scribbles,” she says. A doodle is the first step toward a refined design.

🛠️ Tools for Fashion Design, Drawing, and Pattern Drafting:

- Graphic for iPad

- Apple Pencil

- Adobe Illustrator

- SketchBook

- Accumark Pattern Design Software

- Gemini CAD Systems

- Inkscape

Although she’s outsourcing much of the production to local factories now, Sarah produces all of her own samples by hand, to this day. “I’ve always believed that you should make your own samples if you’re a clothing designer,” she says. This way, you can enter a relationship with a manufacturer with a better understanding of what production might entail. You’re in a better position to negotiate on costs if you’re intimate with the process.

Sarah does, however, advise that your involvement in production should stop at samples. “Focus on being creative, she says. “I fall into a trap of doing custom pieces for customers, and clothing production is such a time suck.”

Clothing production and manufacturing

In the early days, you may not be producing volumes that warrant outside help, but as you scale, a manufacturing partner will let you free up time for other aspects of the business and design. There are a few exceptions—maybe the handmade aspect is a cornerstone of your brand, and you’ll always touch production even as you scale. Growth, though, is generally dependent on outsourcing at least some of the work.

Manufacturing your designs can be accomplished in a number of ways:

- One-of-a-kind/handmade by you

- Made by hired staff or freelance sewers: try Upwork, fashion community groups online, or local college intern programs

- Sewn in your own production facility

- Outsourced to a local factory: try Maker’s Row or MFG

- Produced at an overseas factory

Adrienne Butikofer of OKAYOK is still involved in production because she designed her business that way but has brought on staff to free up time and farms out her dye runs to a factory. In Michigan, Detroit Denim produces clothing in its own manufacturing facility, where it’s able to control the process—at scale.

If you’re starting out from your home, be sure your studio is set up to accommodate flow from one machine to the next, has ample storage, considers ergonomics, and is an inspiring space where you’ll be motivated to spend time.

Alternatively, combat loneliness and save money on equipment by seeking out co-working or shared studio spaces like Sew FYI in LA or Necessary Arts in Guelph, Ontario. Art Connect has a directory for creative spaces in Germany, Spain, London, and New York. Join community groups to find out if a similar space exists in your area.

Ultimately, how you choose to tackle production comes down to a few questions:

- How large are your runs?

- Is “made in America” or “made locally” important to you?

- Are you more concerned with ethical manufacturing or lowest cost?

- How hands on do you want to be in the production?

- Do you plan to scale?

📚 Read more: Home Office Ideas: Brilliant Hacks to Maximize Productivity

Working with clothing manufacturers

In the beginning, Sarah’s line was produced primarily by her own hands, but she began outsourcing some elements to local sewers as she grew. Now, she’s working with factories and taking back her time to focus on building her brand, developing new collections, and expanding her wholesale channel.

Obviously American-made comes with a higher price point, but it’s worth it to me.

For Sarah, closely monitoring the process was important. She also feels that her customer cares about local and ethical production—enough to pay extra for it. “Obviously American-made comes with a higher price point, but it’s worth it to me,” she says. “I think transparency is a big plus.”

When vetting local factories, Sarah believes it’s important to visit each one to get a feel for their practices. She initially requests samples from the factories to inspect the craftsmanship. Her experience working in the corporate world taught her not to put all of her eggs in one basket. She weighs the strengths and weaknesses of each factory and collects her findings in her own database. “Big companies use different factories for different things,” she says. “Maybe there’s a factory that does knitwear better or one that does pants better.”

Fabric sourcing and textile design

Sarah says that fabric sourcing has a lot to do with who you know. Building a network in the industry can help you access contacts for fabric agents, wholesalers, and mills. When she lived in Toronto, she knew the local fabric market and used an agent to get access to fabrics from Japan. But even that route has pitfalls. “In Canada, it was weird, because if you get an agent, everyone’s using that same agent,” she says. ”All of the local clothing lines are all using the same fabrics. ”

All of the local clothing lines are all using the same fabrics. That’s why I really got into honing my textile design skills.

When fabric from all over the world became easier to access online, Sarah began to find it difficult to source unique prints and materials, despite her contacts. Her solution: she began to design her own. “When I got out of fashion school in 2005, you couldn’t just go online and go to Alibaba. Now, lots of people I know do that,” Sarah says. “That’s why I really got into honing my textile design skills.”

Five years ago, Sarah moved from Toronto to Portland, Oregon and found herself rebuilding her network of suppliers and facing a new learning curve. “People on the west coast go to LA to source their fabric,” she says. “I’ve had to go four or five times before I learned where to go, how to order things.”

Sarah learned over time that building personal networks and joining communities of designers has helped her navigate these challenges. Build your own network by looking for local incubators, meetup groups, online communities, or live fashion networking events.

Fashion seasons and timing your collections

The fashion industry operates on a seasonal cycle (fall/winter and spring/summer), and working backward from each season means that development of a collection can start a year or more out. "At Walmart, we were developing two years in advance,” Sarah says. “Corporations tend to design faster, so they’re doing a lot of trend research.” Without the big team and resources, though, independent designers like Sarah are working closer to delivery dates.

Your design and development period and delivery dates depend on your customer and your launch strategy, Sarah says. If you’re selling wholesale, buyers will need to see your collection a month before fashion week.

Try to hold back on the pictures online, because you still want people to be excited when it actually ships in February.

“I showed my spring collection in October, but by the time you show your collection it’s already over,” she says. ”Try to hold back on the pictures online, because you still want people to be excited when it actually ships in February.” Sarah suggests that you have your collection ready for the next season at least six to eight months in advance.

Work backward from your delivery date to establish your design and production timelines. Add dates of important global fashion events, like New York Fashion Week, to your calendar to help set goals.

Seasonality doesn’t have to dictate your collections, however. “It’s always such a shame when I design a beautiful print and I think, ‘I only have this for one season. I only have a six-month window,’” says Sarah. Therefore, she’s inspired to work toward prints that work regardless of season.

Wholesale and consignment

Wholesale played a huge part in the growth of Sarah’s brand in the beginning. After navigating other sales channels, she’s recently returned to a wholesale strategy.

When you’re just starting out, Sarah tells me, a lot of retail stores won’t want to take a chance on you unless you’re open to a consignment agreement, meaning that stores only pay you when an item sells. Wholesale, on the other hand, generally refers to being paid up front for the items.

“If you start with consignment, everybody wins, she says. ”It’s a lot easier for stores to take your whole collection, as opposed to just one or two pieces, because they have nothing to lose.” It’s harder for the designer when you’re not getting money up front, but you can build trust and grow exposure if you’re willing to wait on a payout.

You can’t just have pretty clothes. You have to know every detail.

Approaching buyers is a daunting experience, and Sarah has worked on both sides of the transaction. Her experience looking through the buyer’s lens helped her stand out when she was pitching her own line. Be prepared, she urges. “The first time I pitched my line, I asked myself, ‘What are buyers going to ask me?’” she says. “You can’t just have pretty clothes. You have to know every detail.”

Hitting the pavement was a strategy that worked for Sarah when she was starting out, but I had to wonder: does anyone do anything in person anymore? Sarah thinks there’s still merit in a face-to-face approach, but suggests finding a happy medium. “It’s so easy to send an email,” she says. “But think of a fashion editor or a store owner. How many emails a day do they get?”

While she advocates for face time, Sarah doesn’t recommend an ambush. Start slow, she says. Introduce yourself with a card or a catalog and try to book time to meet later. “There are ways that you can approach people without either accosting them or hiding behind a computer screen.”

📚 Read more:

- Wholesale for Clothing Lines: How to Sell Wholesale to Retailers

- Wholesale to Scale: How One Entrepreneur is Keeping Up With Demand

How to start a clothing line—online

Let’s make sure you have a solid online business idea. Does your clothing line business plan detail how you will handle shipping and fulfillment, packaging, and online customer service? Is your production method able to accommodate single orders? Ready? OK, let’s open your store. It only takes a minute to sign up for a free trial, and we’ll give you some time to play around before you commit. Or if you're ready, you can buy your website domain name and map it straight to your Shopify store with our domain generator.

Ready to create your fashion business? Start your free trial on Shopify.

A professional online store can serve to purposes: it’s a way to sell directly to your potential customers, of course, but also works double duty as your living, breathing lookbook to share with buyers and media.

Choose a Shopify Theme that puts photos first. We suggest themes designed for fashion brands like Broadcast or Galleria, or a free version like Boundless. These themes help photos pop, so make sure you invest in professional photo shoots. For a smaller budget, a simple lighting kit, DSLR camera (or even your smartphone), and some tricks of the trade can help you produce professional-looking DIY shots. Be sure to capture details: fabric texture, trims, and closures.

There are also a wealth of apps in the Shopify App store designed specifically to help fashion brands create personalized shopping experiences and solve common challenges like fit and sizing. Among the best apps to sell clothes, these are a few standouts:

Fashion is an ideal vertical for social selling. Consider reaching your target audience by selling through channels like Instagram and Facebook Shops.

📚 Read more:

- How to Create a Social Media Marketing Strategy for Your Clothing Line

- The Beginner’s Guide to Product Photography

Selling fashion IRL: Markets, pop-ups, and retail

It took Sarah 11 years to be in a position to seriously consider opening her own retail boutique. But it wasn’t a leap—it was a move that she’d been grooming herself to make. Throughout the evolution of her brand, she used local markets like Toronto’s Inland to gain more insight into her customers, test her merchandising, get exposure, and build relationships in the industry.

I was always afraid of opening my own store because of the overhead, especially in Toronto. It just wasn’t attainable.

After her move to Portland, she took her retail experiment to the next level with a three-month pop-up before opening a permanent retail location. “I was always afraid of opening my own store because of the overhead, especially in Toronto,” says Sarah. “It just wasn’t attainable.”

Through the process, she learned that she could use six more hands. She hired a fashion design student to help in the store. “When you have a retail store and a clothing label, as a lot of entrepreneurs do, you just have to learn how to allocate things,” she says. “It’s taken me a long time to learn that, but what I’m paying her to work in the store, my time is worth so much more.”

Since our first interview, Sarah has closed her retail location. “I did not like running it,” she says. The store took her away from the aspect of the business that she loved—designing. One Imaginary Girl still sells direct to customers via its website but has switched much of its focus to wholesale. Sarah now works with Wolf and Badger (NYC and London) and Fox Holt, a boutique focusing on sustainability.

🛠️ More resources to help you make the leap to physical retail:

- Craft Shows & Markets: A Maker’s Guide to Nailing the In-Person Selling Experience

- The Ultimate Guide to Pop-up Shops

- Fleas, Fairs and Festivals: Shopify's Market Directory Helps You Sell Goods IRL

- Models vs. Mannequins: Which Should you use for Your Store?

Project Runway: reality TV vs. reality

Sarah’s experience as a contestant on Project Runway taught her many important lessons about herself and her industry.

While Sarah understands that being reactive in fashion is an asset, she knows she thrives when she has more wiggle room. Because of her development background, she was amazed at the work her fellow competitors could do in a short amount of time. ”For me, it was not a realistic pace at all,” she says. ”It’s a shame that my best work wasn't on national television.”

It’s a shame that my best work wasn’t on national television.

She also faced one of the scariest things any artist has to face: the haters. She was eliminated in the fourth episode when her swimwear didn’t resonate with the judges. The lesson: your audience is not everyone. But she was also surprised to see many supportive tweets from new fans she amassed during the show’s run. “The show taught me that everything comes down to taste,” she says. “No matter what some people think of your stuff, there’s always someone else who likes it.”

What’s next for Sarah? She’s taking her own advice by staying creative and honing in on what she’s best at: design. Sarah says she wants to expand on work she has recently done for brands like Wildfang, Microsoft, and the Hoxton Hotel. “I want to turn Sarah Donofrio into a print go-to.”

One Imaginary Girl is a thriving business because Sarah pursued the dream of it through her lowest lows and let every misstep guide her next pivot. Sometimes those pivots were risks, but, she says, that’s the only way to grow.

Feature illustration by Pete Ryan